At first glance, Cheesman Park is a place of laughter and leisure — a green haven where Denver breathes. But beneath the manicured lawns lies a layered tale. The truth is rooted in the grass, but its bones lie deeper.

This is the story of a park that began as a cemetery… and never entirely stopped being one.

Whispers Beneath the Grass

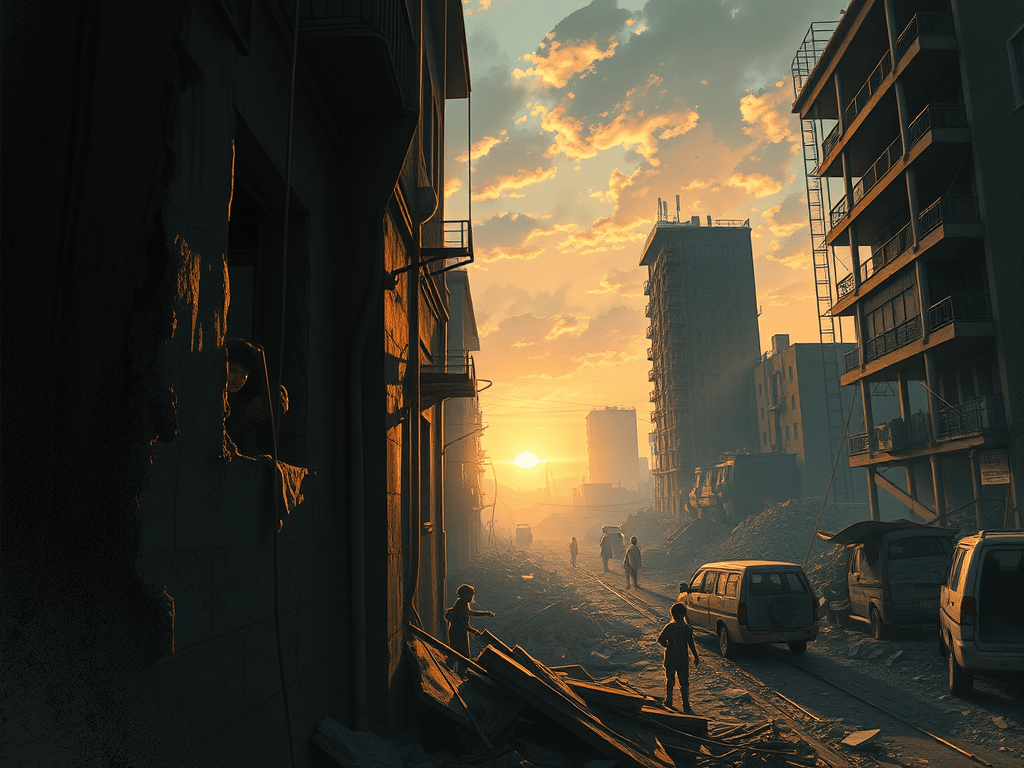

When gold fever drew settlers to the South Platte River in 1858, Denver was little more than a scattering of cabins and tents. Death came quickly to the frontier — by disease, accident, winter, and violence. In 1859, a 160-acre hill east of town was set aside as Mount Prospect Cemetery, later renamed Denver City Cemetery in 1873.

The cemetery was divided into distinct sections: fraternal orders, religious congregations, Civil War veterans, ethnic communities, and the “Potter’s Field” for the poor and unclaimed. Here rested miners killed in the mountains, settlers claimed by typhoid, soldiers from both sides of the Civil War, Chinese immigrants in a segregated section, and those whose names never made it onto a headstone.

By the 1880s, the surrounding Capitol Hill neighborhood was booming, its mansions pressing close to the neglected burial ground. Weeds overtook graves, headstones leaned drunkenly in the wind, and cattle sometimes wandered through. Wealthy residents called it an eyesore, lowering their property values and staining the image of Denver’s most fashionable district.

The pressure worked. In 1890, Congress authorized the city to vacate the cemetery, remove the dead, and create a public park. The land was briefly called Congress Park, its transformation meant to signal progress. But in truth, progress came with a shovel.

Shadows in the Marble

In 1893, the city awarded the contract for removing over 5,000 unclaimed bodies to local undertaker E.P. McGovern. He was paid $1.90 per coffin — the equivalent of roughly $73 in today’s money.

[Sidebar: The Price of a Coffin in 1893]

E.P. McGovern’s $1.90 fee might sound modest, but in 1893 Denver it was a week’s groceries for a small family, two nights in a boarding house, a sturdy pair of leather boots, or nearly a month’s worth of coal for heat.

Paid by the coffin, McGovern had every reason to produce as many “bodies” as possible. That’s why one skeleton could become three or four child-sized coffins — each nail hammered shut worth another $73 in modern terms.

But greed turned the work macabre. McGovern began dismembering corpses and dividing them into multiple child-sized coffins to multiply his profits. Coffin lids were nailed shut in haste, bones protruding from boxes too small to hold them. Workers laughed as they pried open rotting caskets.

On March 19, 1893, The Denver Republican published a scathing front-page exposé titled “The Work of Ghouls.” Public outrage was swift; McGovern’s contract was canceled. The removals stopped midstream. Families who could afford it had already moved their loved ones elsewhere, but thousands — possibly as many as 2,000 — remained in the ground.

The new park grew up over their resting place.

Memory Woven into the Trees

Cheesman Park owes its name to Walter S. Cheesman (1838–1907), a man who had nothing to do with the cemetery scandal but everything to do with Denver’s growth. A New York–born entrepreneur, Cheesman came west in 1861 and built his fortune in railroads, real estate, and water infrastructure. His vision helped supply Denver with clean water through dams and reservoirs — the Cheesman Dam and Reservoir still carry his name.

When he died in 1907, his family donated $100,000 to build a grand neoclassical pavilion in the park. The marble monument, completed in 1908, became such a defining feature that the city renamed the park in his honor. It was a genteel gift — one that gave the park a respectable face, even as its foundation was layered over the forgotten dead.

Landscape architect Reinhard Schuetze shaped the park’s curves and sightlines to erase the rigid rows of the cemetery. He made the land appear natural, fluid, and serene. But history has a way of surfacing. In 2008, irrigation work unearthed burials near the Botanic Gardens. In 2022, a construction crew uncovered a human arm bone. Each time, archaeologists were called, the remains reinterred, and the lawn made pristine again.

Walking with the Dead

Start: West edge of the Great Meadow, facing east toward the white pavilion

Time: 45–60 minutes, unhurried

Note: This is a history walk, not a ghost hunt — but expect the park to keep its own pace

1) The Great Meadow – Once the heart of the cemetery, this open expanse hides hundreds of pauper graves. In the 1880s, this view was marked by leaning headstones and windblown weeds.

2) The Pavilion (Walter S. Cheesman Memorial) – Climb the marble steps gifted by Cheesman’s family. The pavilion’s grandeur hides the fact that it stands above ground never fully cleared of its dead.

3) Southern Edge of the Meadow – Imagine standing here in 1893 as McGovern’s crew worked. The air was heavy with decay, bones scattered like debris, and the public horror building with each exposed grave.

4) East Fence Line to Botanic Gardens – The old Catholic section of the cemetery lies beyond this fence. Even now, the ground sometimes yields reminders of its first purpose.

5) Northeast Curves – Schuetze’s graceful paths follow no grid; their curves deliberately broke the cemetery’s straight, ordered lines.

6) Northwest Corner – Folklore clings here: phantom children at play, footsteps in the grass when no one is there, and that strange, watchful stillness that sometimes settles over the park.

What You Choose to Believe

Maybe the park’s ghosts are real. Maybe they’re only the echoes of a history Denver once tried to bury.

What’s certain is that Cheesman Park is more than a park. It’s a palimpsest — a place where civic ambition, greed, philanthropy, and memory share the same soil. And whether you believe in hauntings or not, you are walking over a chapter of Denver that never truly ended.

Further Reading & Archival Sources

- 42nd U.S. Congress (1872) – Statutes at Large, Ch. 188: “City of Denver may purchase… public lands for a cemetery”

- Denver Public Library – Cheesman Park’s Past Life… as a Cemetery (historical overview & images)

- The Denver Republican, March 19, 1893 – “The Work of Ghouls” (primary reporting on the McGovern scandal)

- Cheesman Park Historic Landscape Assessment – Historic district/National Register documentation

- 9NEWS (2008) – “Bones discovered at Botanic Gardens”

- CBS Colorado (2022) – “Denver Botanic Gardens Crew Uncovers Human Remains”

Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts. Your voice is important to us, and we truly value your input. Whether you have a question, a suggestion, or simply want to share your perspective, we’re excited to hear from you. Let’s keep the conversation going and work together to make a positive impact on our community. Looking forward to your comments!