Thirty-six years after the Beverly Hills murders, the Menéndez brothers’ story still defies clarity. Fear, wealth, and trauma collide in a case that asks whether the line between victim and killer can ever truly be drawn.

The Night Everything Broke

On the night of August 20, 1989, the illusion of security inside Beverly Hills’ gated perfection came undone.

Inside 722 North Elm Drive, José and Kitty Menéndez sat on their living-room couch watching television when two shotguns fired at close range. José was hit first—execution-style—before his wife, Kitty, was struck as she tried to crawl away.

At 11:47 p.m., roughly an hour and forty-five minutes after the shootings, Lyle Menéndez called 911. His voice shook as he cried, “Somebody killed my parents!” while Erik sobbed in the background. To the dispatcher, it sounded like raw panic. To investigators, it sounded rehearsed.

When police arrived at 11:56 p.m., the bodies were cold. Blood had already thickened. The television still flickered in front of them. Detectives quietly noted the timeline didn’t fit the brothers’ story.

What followed would become one of the most polarizing trials in American legal history—a story where grief, greed, fear, and control blurred into a single tragedy.

The Confession That Changed Everything

At first, the brothers lived as though nothing had happened. In the weeks after the murders, they spent lavishly—Rolex watches, a Porsche, restaurants, tennis lessons, overseas travel, and business investments totaling nearly $700,000.

Police grew suspicious. But the confession didn’t come from an interrogation room; it came from a therapy session.

In October 1989, Erik Menéndez told psychologist Dr. L. Jerome Oziel that he and his brother had killed their parents. Oziel secretly recorded parts of their sessions, a decision that would ignite a landmark legal battle.

When the California Supreme Court ruled in People v. Menendez (1992) that portions of the tapes were admissible under the state’s “dangerous-patient” exception, it set a precedent that still stands. The recordings detailed planning, execution, and staging—but not abuse.

Those revelations would later collide with the defense’s emerging claim of lifelong terror.

A Screenplay, a Book, and the Seeds of a Story

Before the murders, Erik had co-written a screenplay titled Friends with a classmate, Craig Cignarelli. The plot centered on a wealthy young man who murders his parents to inherit their fortune. In the wake of the killings, prosecutors seized on it as a chilling precursor—a work of fiction that read too much like foresight.

Around the same period, investigators discovered Erik had been reading a psychology book that cataloged case studies of parricide, particularly those involving sons who claimed abuse as justification. Many of the scenarios described in that text mirrored the same language and trauma patterns the brothers would later present at trial.

Whether the overlap was coincidence or influence remains uncertain. But to prosecutors, it was another thread suggesting calculation: they had studied the narrative before living it.

Fear as a Defense

By the time the first trial began in 1993, the Menéndez defense had shifted entirely toward fear. The brothers described years of sexual and psychological abuse by their father and emotional neglect by their mother. Family members were split—some saw a domineering patriarch, others dismissed the allegations as fabricated.

The defense leaned heavily on psychology: learned helplessness, battered-child syndrome, and cycle-of-abuse theory. But California law recognizes self-defense only when the danger is imminent. Prosecutors argued there was nothing imminent about buying shotguns days before the murders, waiting for their parents to sit down, and firing multiple rounds at point-blank range.

The first trial ended in two hung juries. The second, in 1995, excluded most of the abuse testimony. In 1996, both brothers were convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole.

The Novelli Tapes

In the years between trials, another set of tapes surfaced—this time from Norma “Nora” Novelli, a woman who recorded her conversations with Lyle Menéndez after the first mistrial.

The Novelli tapes, later admitted as evidence, revealed moments of self-awareness, manipulation, and contradictions about the killings and motives. In them, Lyle appeared calculating, discussing public sympathy and strategy. Prosecutors cited these tapes as evidence of image management, further eroding the sincerity of the self-defense narrative.

While not directly related to the abuse claims, the tapes reinforced the perception that the brothers shaped their story as much as they lived it.

New Evidence, Old Questions

In 2023, new material rekindled public attention:

- A 1988 letter written by Erik to his cousin Andy Cano, describing ongoing fear and alleged molestation.

- A sworn statement from Roy Rosselló, a former member of Menudo, alleging that José Menéndez sexually assaulted him in the 1980s.

Defense attorneys argued that both pieces of evidence supported a long-standing pattern of abuse.

But in September 2025, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge denied their habeas corpus petition. The ruling called the evidence “disturbing” but not material enough to change the verdict. It could explain motive, the judge wrote, but not justify homicide.

The law remained unmoved; the culture, less so.

Resentencing and Parole

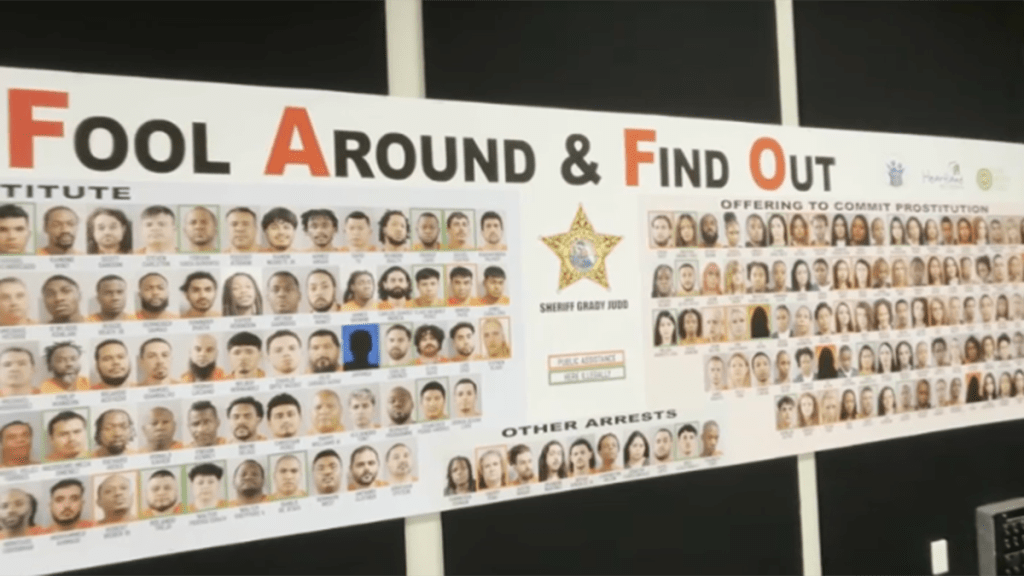

In May 2025, under California’s youth-offender resentencing reforms, both brothers—under 26 at the time of the murders—had their sentences reduced from life without parole to 50 years to life, making them immediately eligible for parole.

At their August 2025 parole hearings, the brothers presented as rehabilitated men: educated, spiritual, and reflective. But the board cited ongoing institutional violations—contraband phones, communications breaches, and minimization of culpability.

District Attorney Nathan Hochman maintained his opposition, stating that release would only be considered when the brothers “fully and unequivocally admit to every part of their crime.”

Both were denied parole for three years, though eligible for review after eighteen months.

Fear, Control, and Inheritance

Forensic psychologists have long described the Menéndez case as a mixed-motive homicide—part fear, part entitlement. The evidence supports both.

There are signs of genuine trauma: the Cano letter, fractured family dynamics, and testimony of humiliation. But the brothers’ financial behavior, the screenplay, and their calculated lies suggest that fear was not of death—it was of disinheritance.

If their father’s control defined them, his money sustained them. When he threatened to cut them off, they may have perceived not just loss, but annihilation.

In that sense, their act was both rebellion and reclamation—a violent refusal to lose power.

The Lies That Remain

From the night they staged a burglary to the fabricated alibi about movie tickets and ice cream, deception followed every step. Prosecutors cataloged more than a dozen lies; the brothers have admitted to only a few.

In parole hearings, those omissions carry weight. Rehabilitation requires full transparency, and after thirty-six years, both men still leave gaps between confession and truth.

Why It Still Matters

The Menéndez story continues to divide public opinion because it touches the fault line between accountability and empathy. It asks whether a person can be both a victim and a perpetrator, and whether fear—emotional or financial—can ever justify violence.

It was America’s first courtroom spectacle of the television age: raw, glamorous, and endlessly dissected. But decades later, it reads less like a tabloid tragedy and more like a psychological case study—of trauma weaponized, privilege corrupted, and the gray space where both collide.

The Unanswered Question

The truth is likely not singular. Abuse may have been real; the fear, exaggerated; the motive, layered.

The law answered what it could—intent, planning, premeditation. The rest remains suspended between psychology and morality.

Inside that unresolved space lies the lasting grip of the Menéndez case: two brothers, one house, and a silence that still divides what we can prove from what we believe.

Sources & Records

- People v. Menendez, 3 Cal.4th 435 (Cal. 1992): Ruling on psychotherapist–patient privilege and admissibility of Oziel tapes.

- Los Angeles Superior Court Habeas Ruling (Sept 2025): Denial of new-trial petition; findings on 1988 Cano letter and Rosselló affidavit.

- Los Angeles Times archives, March 9, 1990: “Menendez Friend Says Screenplay Mirrors Parents’ Slayings.”

- Guardian, May 2025 – “Judge Resentences Menendez Brothers, Making Them Eligible for Parole.”

- Reuters, Mar 2025 – “DA Says Menendez Brothers Must Fully Admit Lies to Be Freed.”

- PBS NewsHour, Aug 2025 – “Parole Hearings Shed Light on Rehabilitation Debate.”

- ABC News, Aug 2025 – “Lyle Menendez Denied Parole; Board Cites Rule-Breaking.”

- CBS 48 Hours, 2023 – “Menendez Brothers Await Decision They Hope Will Free Them.”

- California Penal Code §198.5 – Definition of imminent threat and lawful self-defense.

- Los Angeles County DA Filings (Feb–Aug 2025): Opposition to habeas relief; enumeration of false statements and evidentiary analysis.

- DA Exhibit 10 – Norma Novelli Transcript (Los Angeles County, 1993).

Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts. Your voice is important to us, and we truly value your input. Whether you have a question, a suggestion, or simply want to share your perspective, we’re excited to hear from you. Let’s keep the conversation going and work together to make a positive impact on our community. Looking forward to your comments!