April 9, 2025

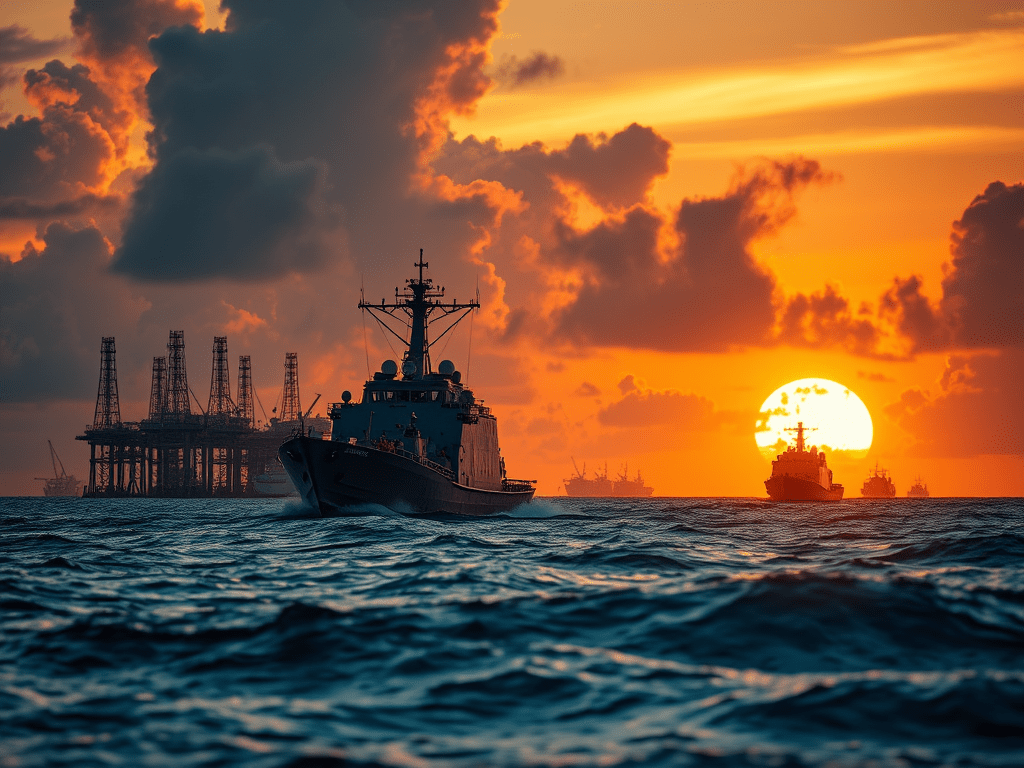

The Euro-Atlantic security landscape is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the militarization of space and the rapid advancement of technologies that blur the lines between terrestrial and extraterrestrial conflict. On April 10, 2024, Dr. Celeste Wallander, Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, and General Christopher G. Cavoli, Commander of U.S. European Command (USEUCOM), testified before the U.S. House Armed Services Committee, revealing the escalating threats posed by Russia’s space capabilities and the strategic responses from the U.S. and NATO. From anti-satellite weapons to orbital nuclear threats, Russia’s advancements challenge the stability of the region, while the U.S. and its allies race to secure their space assets and maintain deterrence. This article delves into the technologies at play, their historical context, geopolitical implications, ethical and legal challenges, and what the future might hold for this new frontier of global security.

Russia’s Space Arsenal: A Multi-Domain Threat to Euro-Atlantic Stability

Russia’s military capabilities in space have become a focal point of concern, as highlighted by both Wallander and Cavoli. Despite significant losses in Ukraine—315,000 casualties, 2,000 tanks, and $211 billion in direct costs—Russia’s space capabilities remain fully intact, posing a “serious risk” to U.S. and European security, according to Wallander. Cavoli emphasized that these capabilities have “lost no capacity at all” during the conflict, underscoring their resilience and strategic importance.

Anti-Satellite Weapons and Orbital Threats: Russia’s counterspace arsenal includes anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons, which can physically destroy satellites in orbit. A notable example is the 2021 test of a direct-ascent ASAT missile that destroyed Kosmos-1408, creating over 1,500 pieces of trackable debris that threatened the International Space Station. This test demonstrated Russia’s ability to target satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO), where most U.S. and NATO assets reside, including those for communication (e.g., SATCOM), navigation (e.g., GPS), and intelligence (e.g., reconnaissance satellites). More alarming is Cavoli’s mention of “orbital nuclear weapons,” potentially referring to a modernized Fractional Orbital Bombardment System (FOBS). Historically tested in the 1960s, FOBS allows nuclear warheads to be placed in orbit, enabling unpredictable strikes that bypass traditional missile defenses by approaching from any direction, including over the South Pole. Such a system, if operational, could deliver a nuclear payload with little warning, threatening not just military satellites but civilian infrastructure dependent on space, such as global communications and weather forecasting.

Nuclear-Powered Systems: Russia is also developing nuclear-powered systems that extend its reach across domains. The 9M730 Burevestnik (NATO: SSC-X-9 Skyfall) is a nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed cruise missile with a near-unlimited range, potentially exceeding 20,000 km. Powered by a small nuclear reactor, it can loiter for days or take circuitous routes, making it difficult to detect and intercept. However, its development has been marred by failures, including a 2019 test explosion that killed five scientists and released radiation, raising concerns about its reliability and safety. The Poseidon (Status-6) is another nuclear-powered system—an autonomous underwater vehicle launched from submarines, capable of carrying a 2-megaton warhead (or larger) to trigger radioactive tsunamis against coastal targets. Operating at depths up to 1,000 meters and speeds of 100 knots, it’s nearly impossible to intercept with current technology. While not space-based, these systems complement Russia’s space capabilities by targeting U.S./NATO vulnerabilities from multiple domains, creating a layered threat.

Hypersonic and Cyber Capabilities: Russia’s nuclear-armed hypersonic boost glide vehicles, such as the Avangard, travel at speeds exceeding Mach 20 (over 24,000 km/h), maneuvering unpredictably to evade missile defenses. Launched atop ICBMs, the Avangard operates in the upper atmosphere, blurring the line between space and terrestrial domains. Its ability to change trajectory mid-flight makes it a significant challenge for U.S. missile defense systems like Aegis or THAAD. Additionally, Russia’s cyber capabilities, unaffected by the war, are a force multiplier. Groups like Fancy Bear (APT28), tied to Russia’s GRU, have targeted NATO networks with malware, phishing, and DDoS attacks, as documented by CrowdStrike. These cyber operations can amplify space disruptions by targeting ground-based command-and-control systems, potentially blinding U.S./NATO forces if satellites are attacked.

Long-Range Precision Fires and Production Surge: Russia has increased production of ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and drones, supported by imports from Iran and North Korea. Cavoli notes Russia now produces 1,200 tanks and 3 million artillery shells/rockets annually—triple initial U.S. estimates. Systems like the Kalibr cruise missile (range ~2,500 km) and Iskander ballistic missile (range ~500 km) rely on space-based navigation (e.g., Russia’s GLONASS) for precision targeting, enhancing their effectiveness against European targets. This production surge, combined with space-enabled targeting, allows Russia to sustain its war effort despite sanctions, posing a direct threat to NATO’s Eastern Flank.

Historical Context: Space as a Cold War Legacy and Modern Battleground

The militarization of space is not new—it dates back to the Cold War, when the U.S. and Soviet Union raced to dominate this frontier. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, signed by both nations, banned the placement of nuclear weapons in orbit and restricted space to “peaceful purposes,” but enforcement has been weak. The Soviet Union’s FOBS program, active in the 1960s, was a precursor to today’s orbital nuclear threats, designed to evade U.S. early warning systems by launching over the South Pole. The U.S. countered with its own ASAT programs, like the 1985 test of an ASM-135 missile that destroyed a U.S. satellite, but largely abandoned such efforts after the Cold War, focusing on space for communication and intelligence rather than weaponization.

Russia’s recent ASAT tests, including the 2021 Kosmos-1408 incident, signal a return to Cold War-style space competition, but with modern stakes. Satellites now underpin global economies—supporting everything from GPS navigation to financial transactions—making them high-value targets. The U.S. Space Force, established in 2019, reflects this shift, with its mission to “secure our nation’s interests in, from, and to space,” as stated on its official website. NATO’s 2021 recognition of space as an operational domain, followed by the 2023 NATO Space Symposium, further underscores the Alliance’s pivot to address these threats, driven by Russia’s actions in Ukraine and beyond.

U.S. and NATO’s Technological Countermeasures: Securing the High Ground

In response to Russia’s space threats, the U.S. and NATO are enhancing their capabilities, with a particular focus on space as a theater of operations. Wallander and Cavoli detailed several initiatives to counter these risks and maintain deterrence in the Euro-Atlantic region.

Space Component Headquarters and USSPACEFOR-EURAF: The U.S. has established a Space Component Headquarters in Europe and stood up the United States Space Forces Europe and Africa (USSPACEFOR-EURAF) at Ramstein Air Base in December 2023, as Cavoli noted. This new Space Force component creates a “networked, joint-space architecture,” overseeing satellite operations (e.g., GPS, missile warning via SBIRS), space surveillance (tracking threats with systems like the Space Fence), and integration with NATO allies’ space assets. USSPACEFOR-EURAF collaborates with allies like the UK, which operates the Skynet satellite system, and France, with its Syracuse satellites, to ensure resilience against Russia’s counterspace threats. This move also supports NATO’s Space Centre of Excellence in Toulouse, France, established in 2021 to enhance allied space interoperability.

Advanced Fighter Squadrons and Space Integration: The U.S. is transitioning from F-15C/Ds to F-35 fighter squadrons at RAF Lakenheath, with one squadron completed in April 2024 and another due by August 2025. The F-35’s stealth, advanced sensors (e.g., AN/APG-81), and networked data fusion rely on satellite communications (e.g., Link 16) for real-time battlefield awareness, making space protection critical to their effectiveness. These squadrons enhance air superiority and deterrence, countering Russia’s long-range precision fires, which include Kalibr cruise missiles and Iskander ballistic missiles, both guided by GLONASS.

Agile Combat Employment (ACE) and Prepositioned Stocks: Cavoli highlighted the use of Agile Combat Employment, dispersing air assets across smaller, flexible bases in Poland and the Baltics, supported by satellite-enabled logistics. Army Prepositioned Stocks (APS) in Poland, completed in May 2024, hold equipment for two armored brigade combat teams, including M1 Abrams tanks, Bradley vehicles, and HIMARS rocket systems (range ~300 km with GPS-guided munitions). These stocks are maintained via satellite-monitored logistics, ensuring rapid deployment. ACE and APS reduce vulnerability to Russian missile strikes and space-based targeting, allowing NATO forces to remain “dynamic, survivable, and lethal” even if satellites are disrupted.

Cyber and Strategic Deterrence: USEUCOM’s Cyberspace Operations Division, coordinated with U.S. Cyber Command, defends networks against Russian cyber threats, such as those from Fancy Bear (APT28), which has targeted NATO with malware and DDoS attacks. The U.S. is also modernizing its nuclear systems, including B-61 bombs in Europe and Trident submarine-launched ballistic missiles, with space-based early warning (e.g., SBIRS) ensuring deterrence against Russia’s nuclear advancements. These systems rely on space for detection, tracking, and response coordination, highlighting the interconnectedness of space and nuclear strategy.

The Axis of Adversaries: A Global Network of Technological Support

Russia’s technological edge is amplified by its partnerships with China, Iran, and North Korea, forming what Cavoli calls a “block of adversaries” with “interlocking strategic partnerships.” This coalition enhances Russia’s capabilities across domains, creating a networked threat that challenges U.S./NATO dominance.

China’s Role: China provides nonlethal assistance to Russia, including drones and computer chips, reliant on its BeiDou satellite navigation system, which rivals GPS and GLONASS. BeiDou, with 35 satellites in orbit, offers global coverage and supports China’s military and commercial operations, potentially aiding Russia’s drone targeting in Ukraine. China also invests in European infrastructure, such as Huawei 5G networks, which could enable monitoring or disruption of NATO communications if exploited. Wallander notes that these investments in ports and telecoms threaten NATO’s logistics, military mobility, and security, as they could be used to gather intelligence or sabotage operations during a crisis.

Iran’s Contributions: Iran supplies Shahed-136 kamikaze drones and ballistic missiles to Russia, with a $1 billion deal for 6,000 drones by 2025. The Shahed-136, with a range of ~2,000 km, is GPS-guided (likely via GLONASS in Russian use), allowing precise strikes on Ukrainian targets. Iran’s Fateh-110 ballistic missiles (range ~300 km) further enhance Russia’s long-range strike capacity, complementing its space-enabled targeting systems.

North Korea’s Support: North Korea has delivered 6,700 containers potentially holding 3 million artillery shells, as Cavoli notes, overwhelming Ukraine’s defenses through sheer volume. These 152mm and 122mm shells, while basic, are mass-produced and can be used with Russian targeting systems, which rely on GLONASS for accuracy. This support indirectly bolsters Russia’s space-enabled precision strikes, as artillery barrages create opportunities for more precise, satellite-guided attacks.

Historical Context: From Cold War to Modern Space Race

The militarization of space is a legacy of the Cold War, when the U.S. and Soviet Union raced to dominate this frontier. The 1957 launch of Sputnik by the Soviet Union marked the beginning of the space race, followed by the U.S.’s Explorer 1 in 1958. Both nations developed ASAT capabilities—the Soviet Union tested FOBS in the 1960s, while the U.S. conducted an ASAT test in 1985 with an ASM-135 missile, destroying a U.S. satellite. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty banned nuclear weapons in orbit and restricted space to “peaceful purposes,” but enforcement has been weak, as evidenced by Russia’s recent tests.

The post-Cold War era saw a shift—space became a domain for communication, navigation, and intelligence, with the U.S. and NATO relying heavily on satellites for military operations. The 2007 Chinese ASAT test, which destroyed a weather satellite, and Russia’s 2021 Kosmos-1408 test signaled a return to space competition, prompting the U.S. to establish the Space Force in 2019. NATO’s 2021 recognition of space as an operational domain, followed by the 2023 NATO Space Symposium, reflects the Alliance’s pivot to address these threats, driven by Russia’s actions in Ukraine and its broader strategic ambitions.

Geopolitical Dynamics: A Global Space Race with High Stakes

The emphasis on space capabilities reveals a new geopolitical dynamic—a global space race with high stakes for Euro-Atlantic security. Russia’s partnerships with China, Iran, and North Korea form a networked threat that spans domains, from space to cyber to conventional warfare. China’s BeiDou system, with 35 satellites, rivals GPS and GLONASS, supporting its military and commercial operations while aiding Russia’s drone targeting in Ukraine. Iran’s drones and North Korea’s artillery shells, guided by space-based systems, amplify Russia’s reach, creating a coalition that challenges U.S./NATO dominance.

Meanwhile, the U.S. and NATO are racing to secure their space assets, with initiatives like USSPACEFOR-EURAF and NATO’s Space Centre of Excellence in Toulouse. However, the U.S.’s defensive posture—lacking offensive ASAT systems in the statements—suggests a lag behind Russia’s innovations. China’s investments in European infrastructure, such as Huawei 5G, further complicate the landscape, potentially enabling espionage or sabotage that could disrupt NATO’s space-dependent operations.

Ethical and Legal Challenges: Navigating the Militarization of Space

The militarization of space raises significant ethical and legal challenges. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty prohibits nuclear weapons in orbit, but Russia’s development of orbital nuclear systems, if confirmed, would violate this agreement, escalating tensions and risking a new arms race in space. The treaty’s “peaceful purposes” clause is increasingly strained, as ASAT tests by Russia, China, and historically the U.S. create debris that endangers all space users, including civilian satellites critical for global communications, weather forecasting, and disaster response.

Ethically, the weaponization of space threatens global equity—space has been a shared domain for scientific advancement, but its militarization could prioritize the interests of major powers over smaller nations. The potential for space-based conflicts to cause collateral damage on Earth—e.g., through radioactive tsunamis from Poseidon or disrupted communications from ASAT strikes—raises questions about the moral responsibility of nations developing these technologies. Transparency in space activities, as advocated by groups like the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), is crucial to prevent escalation and ensure space remains a global commons.

Future Scenarios: What Lies Ahead for Space Security?

Looking ahead, several scenarios could shape the future of space security in the Euro-Atlantic region:

- Escalation Scenario: If Russia deploys orbital nuclear weapons or conducts another ASAT test, it could trigger a U.S./NATO response, potentially leading to a new space arms race. The U.S. might develop its own ASAT systems, escalating tensions and risking a conflict that spills into space, with catastrophic consequences for global satellite networks.

- Deterrence Scenario: The U.S. and NATO could focus on hardening their space assets—e.g., deploying more resilient satellites like the Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared (Next-Gen OPIR)—and enhancing cyber defenses to deter Russian attacks without direct confrontation. This would require increased investment in space infrastructure, as Cavoli and Wallander urge.

- Cooperation Scenario: International pressure, led by the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), could lead to new treaties banning ASAT tests and orbital weapons, fostering cooperation to manage space debris and ensure equitable access. However, Russia’s current trajectory makes this less likely without significant diplomatic breakthroughs.

Transparency and the Path Forward

The race for space supremacy underscores the urgent need for transparency in military advancements and their implications. Russia’s development of anti-satellite weapons and orbital nuclear systems, if unchecked, could destabilize global security, while the U.S./NATO’s response must balance innovation with allied cohesion. As space becomes a battlefield, we must advocate for clear policies on its militarization, ensuring that technological advancements serve humanity rather than endanger it. International cooperation, robust legal frameworks, and public accountability are essential to prevent space from becoming the next arena of conflict. What role should space play in future security strategies? Share your thoughts!

Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts. Your voice is important to us, and we truly value your input. Whether you have a question, a suggestion, or simply want to share your perspective, we’re excited to hear from you. Let’s keep the conversation going and work together to make a positive impact on our community. Looking forward to your comments!